Back to the future

Place, time and the idea of parish

Its a year today since my last book In the Fullness of Time came out. I’m going to start this Substack with a series of reflections on the themes of that book. But not as a kind of summary, least of all cut and paste, more of a freeform recapitulation to develop a conversation. The issues of decline, anxiety, change and innovation in the church continue to circle and develop. Since I wrote my book I’ve been engaging with writers such as Dougald Hine, Chris Smaje, Vanessa Andreotti and Elizabeth Oldfield. These writers engage with the death of a culture, of an epistemology, of a way of attending to the world, which certain forms of church, held very dear by many, are very much entangled with. On the other hand research such as A Quiet Revival suggests something strange afoot in Christian religious practice. Young adults reading the Bible, praying, pitching up at church, looking for meaning (some might say) in a culture failing to offer it. Some may pounce on that research as a signal that all is well, the tide is turning, stick with tradition and all will be well. Others (myself included) can’t offer such confidence. Something much stranger an unpredictable is occurring which needs our ongoing attention more than our swift conclusion.

So things have moved on in my own thinking as much as in this conversation about what it means to be a Christian communal witness in the world. I am going back to these themes then not as a communication of what I think is right, but more as a stepping back into the flow of this conversation in the hope that we might keep finding new insight.

Death was where it all began. The death of a church. A phone call from my mother to say that the church in the little village I grew up in had closed. This was a church I had not gone to. Nor had my family. It existed in a strange cultural and temporal bubble at the end of the road. Except for a row of affordable cars parked down our lane on a Sunday morning this parish church had little or no impact on our lives. And yet its demise struck me quite powerfully. I knew that it was another blow to the life of a village community that thrived on such nodes of social capital as the church, the village hall, the village shop, the local pub. The wife of the local vicar (who had researched what had happened) told me that, in effect, the final rites of the church were declared when a fight for the resources to run the village hall and the church ended in favour of the village hall.

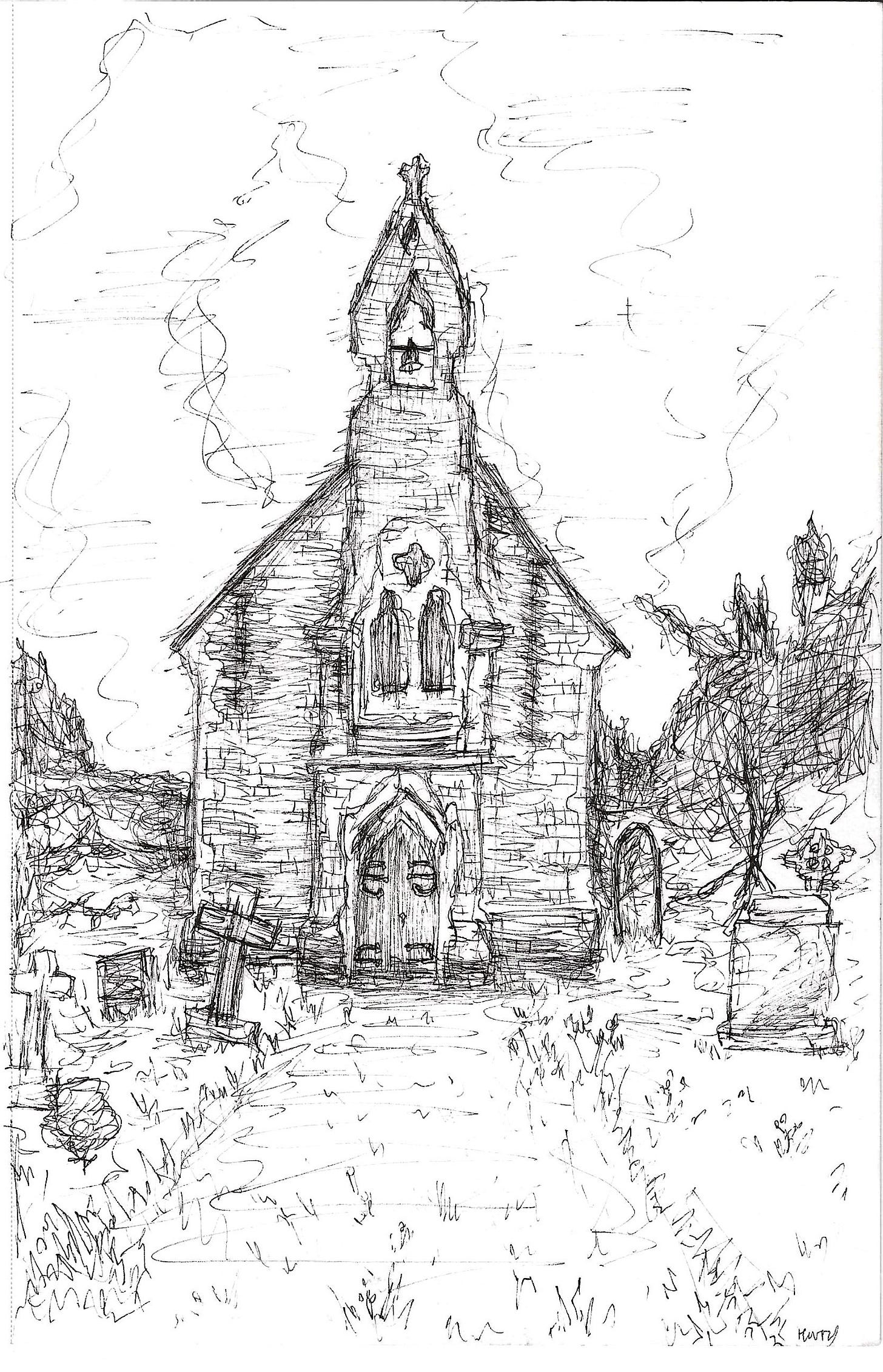

When I returned to this village where I grew up I found the church sitting quietly, in the the shadow of its fate, at the end of a path now crowded with cowslips and in a churchyard in which the headstones were starting to lean into the ground like bad teeth. In the midst of these errant headstones however was one fresh upright one. It was to a Gordon Ralph - and on it the inscription ‘Farmer of this parish’.

Mr Ralph was a farmer from a long line of Ralphs who farmed in that village. His garden hosted the village fete most years. His wife ran the WI. The warp and weft of village life, hall, parish, land, was threaded with this family’s contribution. And I guess what struck me more than anything was the phrase ‘of this parish’ - a phrase that absolutely summed up Ralph Gordon’s life. Yet one that already seemed an anachronism. What present or future lives might be summed up in such a way? Its hard to imagine.

Parish. A form. An idea. A vocation. Is in a fragile state. Andrew Rumsey describes parish as ‘a threefold cord of soil, soul, and society’. A cord which is unravelling in our times. And part of that unravelling is not because there aren’t people in our church buildings to maintain the living soul of it. My conversations with many rural vicars suggested that as a percentage of population many churches were doing quite well. It is more the resources; the time, the energy, the administrative demands, of parishes which it is hard to sustain.

Much of the debate around the demise of rural parishes thus focusses inevitably on the buildings that are a legacy of the parish ideal. There is deep love and a significant cultural capital associated with these buildings. And there is a complex relationship between such buildings and the corporate faith they were designed to enable. ‘Buildings have a ministry’ one vicar said to me. Do they? Perhaps. But perhaps only as part of a complex relationship with a living tradition and with a community that seeks to keep such a tradition alive in the present and for the future.

And perhaps this is where the real crisis for the vocation of parish lies. It lies in the timelessness and placelessness of late modernity. It lies in a culture which turns everything into an individual possession to the exclusion of the other, and to the devaluing of particularity and community. And which turns history into ‘the past’, a negative landscape to be built over in pursuit of progress toward the future.

Parish church buildings, this extraordinary legacy of local love and loyalty, may well continue to face the inevitability of closure in many places. They may become fallow places, set aside for a time, within the soil of culture which struggles to see their relevance. In the meantime there is a ministry of witness for the church in rural places, to continue to be a prophetic embodiment of the value of place and time. To be a community that witnesses to the kind of life that embodies the sacredness of place and time, and expresses that life as a communal invitation, not an individual possession.